Products You May Like

It’s not the world’s only active volcano to attract tourists — countries from Indonesia to Iceland regularly host visitors willing to dice with danger in their efforts to glimpse the natural spectacle of a smoldering or lava-spewing peak.

“Handle with scare” — a brochure used to promote tours of White Island.

John Malathronas

But Monday’s tragic events have spotlighted the tourism industry that’s built up around White Island and other volatile attractions.

Perhaps emblematic of the willingness of both tourist and tour company to dance around the potentially lethal risks involved, is some of the material that has been used to promote White Island in the past.

During a visit made by this writer in 2006, it was being heavily marketed on the perils that tourists would face via literature that now seems toe-curlingly bad, particularly in light of this week’s deaths.

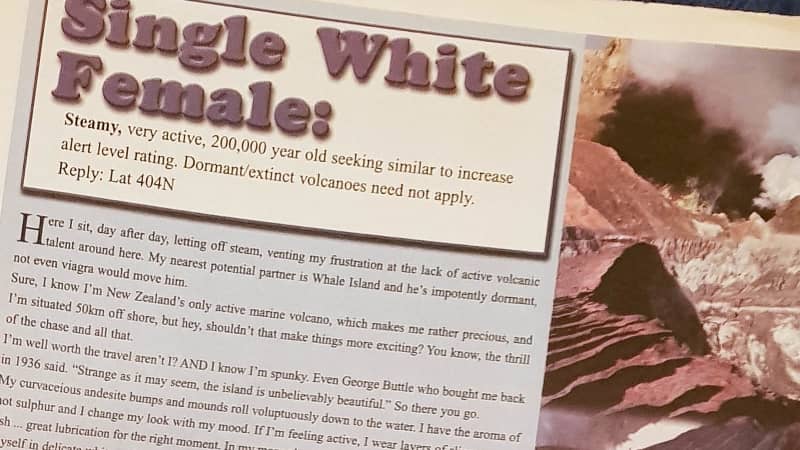

“Single White Female,” reads the headline on a jokey advertorial promoting tours of the volcano that’s written in the style of a lonely hearts column.

“Steamy, very active, 200,000-year-old seeking similar to increase alert level rating,” the piece, credited to a local tour guide, said. “Dormant/extinct volcanoes need not apply.”

It goes on: “My curvaceous andesite bumps and mounds roll voluptuously down to the water. I have the aroma of hot sulphur and I change my look with my mood. If I’m feeling active, I wear layers of slippery grey ash…”

The lonely hearts ad isn’t what tourists to New Zealand would’ve seen just before Monday’s eruption. It appears on the back of a 32-page brochure-slash-newspaper, Discover White Island, that was originally printed in 2003 but being distributed at the time of my visit.

‘Handle with scare’

“Single White Female” — a joke lonely hearts ad used to promote the volcano.

John Malathronas

White Islands Tours — which ceased operations after the December 9 eruption — wasn’t downplaying the risk of visiting the island — headlining the newspaper distributed in 2006 with bold red letters that screamed: “Volcano, handle with scare.”

For backpackers and other thrill seekers touring New Zealand, this whiff of danger has placed White Island firmly on adventure itineraries alongside bungee jumping, jetboating and white water rafting.

It was only when I boarded the tour boat and signed a disclaimer that absolved anyone but myself of any responsibility that the reality of the trip’s dangers hit home, but not enough to dissuade me or my fellow tourists from continuing.

Visitors were equipped with gas masks for a tour of the island.

John Malathronas

Although my visit was incident-free, it would’ve been more or less identical to that experienced by those caught up in this week’s disaster, right up until the point when the volcano erupted.

En route to the island, a school of dolphins appeared in the swell alongside the boat as our guide distributed gas masks and hard hats.

We were then given some basic facts and figures about our destination. Its size — 11 miles by 10 miles. And its history: bought by a man called George Buttle in 1936. The island is still a private reserve belonging to the Buttle Family Trust.

According to my notes from the trip, the guide stressed that the volcano was “very much alive,” and that the terrain we would be crossing had been formed relatively recently during a period of near-continuous volcanic activity between 1975 and 2000.

“The activity level now stands at one,” he said. “Three means there’s constant emissions. Five signals disaster. But remember: We can never rule out an eruption.”

“The danger comes from the main crater that’s covered by a shallow lake. An eruption would lead to a steam explosion and scald us to death.”

New Zealand monitoring service GeoNet operates a five-point alert system for volcanoes. One means minor volcanic unrest, five means major volcanic eruption. At the time of Monday’s eruption, it was set to two — minor to heightened volcanic unrest — an acceptable level for tours to continue under existing safety guidelines.

Corrosive air

After a couple of hours sailing, our party landed at White Island’s Crater Bay, where we were greeted by what looked like an alien landscape.

The sea was lemon yellow, the rocks cinnamon brown, the sand pitch black and the air thick with the smell of an open latrine.

What was eerie, though, was the silence. I was expecting a roar, at least a muted grumble, but no, the island was silent.

The island resembles an alien landscape.

John Malathronas

“Wrap everything, especially your camera, in plastic bags,” the guide warned. “Take it out for a photo and put it back in again. The air is corrosive.”

“What about us?” I asked.

“You are alive and have repair mechanisms in place. Your lenses don’t.”

The guide led us through the skeletal, rusty remains of a factory. Despite the risks, people have been mining sulfur here on and off since the 1880s.

“Back in September 1914 a sudden slag flow buried the living quarters and killed 10 miners,” we were told. “Only their cat survived.”

“Mining resumed in 1923 but was abandoned in the 1930s. It became too dangerous to continue.”

At some point he showed us a rivulet running through the ground.

“It’s been raining, so you’ll see a lot of small streams,” he said. “Step over them. They’re pure battery acid. Stick to the path and follow me.”

With pewter-gray ash and scoria covering much of the land; the scene could’ve been described as lunar if it weren’t for the mist over the steam vents.

These vents came in every shade of yellow — from banana to butterscotch and all variations in between.

“Don’t go anywhere near the vents,” our guide said. “The coolest ones clock 95 C (100 F). The superheated ones can reach 200 C (400 F). Some go deep down to 600 feet below sea level.”

Some of the big vents have names, we were told. There was Gilliver, Rudolf and Donald Duck.

Others were large enough to be classified as craters, with names like Big John or Noisy Nellie.

‘Everything rusts’

Writer John Malathronas on White Island.

John Malathronas

Our guide showed us debris from an eruption in 2000.

“It only lasted for 12 seconds but spewed out five-foot-long rocks hundreds of feet away,” he said. “I was here three days later. The rocks were still warm and you could pry them apart like toffee.”

At some point, we reached a white line painted on the ground and were told to stop.

“From here on, the crust is thin,” the guide said. “Walk further and the ground might give in under your feet.”

In front of us lay the main crater cloaked under a vapor cloud, a gate to the center of the Earth.

Boat trips have long carried visitors to White Island.

John Malathronas

We stood there silently, taking photos before slowly heading back, skirting the white line.

Back on the boat, the guide changed his sneakers. He used a separate pair just for White Island. “Plastic laces, holes with no metal eyelets; everything rusts there,” he said.

On the return journey to Whakatane, we were served warm soup to soothe our stinging throats followed by a meal of rice and baked fish.

This time the entertainment came from above as a company of gannets nosedived into the sea with spectacular plunges.

“Despite the eruptions, this gannet colony is well established,” the guide said. “Amazingly, it’s on the safest part of the island. This is where the miners built their cabins when they returned in the 1920s.”

Today, looking back at my diary of my 2006 trip, I’m struck by a quote I scribbled down that’s attributed to the island’s late owner, George Buttle.

He supposedly said: “Strange as it may seem, the island is unbelievably beautiful.”

In its own extra-terrestrial kind of way, it was. And I’m glad I’ve been there.

But like so many visitors over the years, I know that I’ve played with fire for the fun of it.

Others weren’t so lucky.