Products You May Like

A line of Boeing 737 fuselages, eventually bound for Boeing’s production facility in nearby Renton, Wash., sit on flatcar rail cars at a rail yard Tuesday, April 9, 2019, in Seattle.

Elaine Thompson | AP

A year ago, Boeing executives were trying to convince Wall Street investors they could ramp production of their best-selling 737 Max plane to record levels as demand surged.

“The Max production ramp-up continues,” Chairman and CEO Dennis Muilenburg explained on an Oct. 24, 2018 conference call. There was tremendous “upward market pressure” on the manufacturer’s 737 production rate, meaning Boeing was having trouble keeping up with orders for the company’s hottest-selling plane (which was sold out until the mid-2020s). Muilenburg assured analysts on that earnings call that the company would be churning out more planes next year.

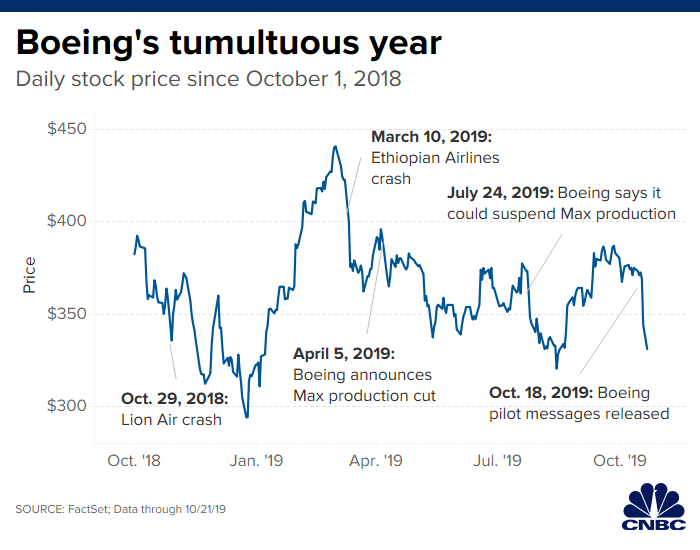

Five days after the call, one of the jets flown by Lion Air with 189 passengers and crew crashed outside of Jakarta minutes after take off, followed by another in Ethiopia with 157 aboard less than five months later. There were no survivors.

Now Boeing’s management is struggling to convince Wall Street — and Washington — that the plane is safe enough to fly.

Company in crisis

Falling profits

Boeing will face investors on Wednesday when it reports third-quarter earnings before the market opens. Analysts polled by Refinitiv expect a nearly 42% drop in per-share earnings from a year ago and a 23% drop in revenue to $19.4 billion. For the full year, analysts expect profits to fall 81% from 2018.

The crashes have already cost Boeing more than $8 billion, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch, and those losses could rise if the grounding wears on. With sales and deliveries of the Max planes nearly dried up this year, rival Airbus is set to take the title of the world’s largest aircraft manufacturer this year.

Boeing halted deliveries of the planes shortly after the grounding, and slashed production by 20% to 42 a month. Expectations of when the planes could return to service has continued to slip — no U.S. airline with Max planes in their fleet expect the jets back before next year.

Slipping timeline

Ron Epstein, Boeing analyst at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, on Friday said he expected Boeing to resume Max deliveries in March.

That was before bombshell messages from 2016 and 2017 were released later that day that sent Boeing’s stock tumbling. In those messages former top Boeing pilot pointed to concerns about the 737 Max after he flew in a simulator, saying a system on board was “running rampant.” An email showed the same pilot told the FAA to delete a flight-control system known as MCAS — the same one that would later be implicated in both crashes — from manuals. In a separate email, the pilot boasted about “jedi-mind tricking” regulators into approving the training material.

“We thought [the March estimate] was conservative when we put it out but now it looks optimistic,” Epstein said in an interview on Monday, after the messages were released. Epstein estimates that sales of the 737 Max accounted for 40% of Boeing’s profit and a third of its cash flow.

FAA complains

Boeing later said it provided the messages to “government investigators” early this year, but the FAA complained that company took months before it turned them over to the agency. Boeing said it repeatedly told the FAA and other regulators about the expanded abilities of the automated flight-control system.

“We understand entirely the scrutiny this matter is receiving, and are committed to working with investigative authorities and the U.S. Congress as they continue their investigations,” Boeing said in a statement on Oct. 20.

After the messages were released, Boeing’s stock fell nearly 11% over the next two days in a rout that knocked more than $21 billion off of the company’s market value. Several banks, including UBS, BofA, and Credit Suisse either downgraded Boeing’s stock or lowered their price targets.

Eyes on certification

Pilots complained they didn’t know the flight-control system, MCAS, existed until after the first crash. That system malfunctioned during both fatal flights and repeatedly pushed the nose of the planes downward. It’s designed to to prevent an aircraft from stalling when the nose is pointed too high.

Boeing has developed a software fix for the MCAS aimed to make it easier to control with more redundancies built in, but regulators haven’t signed off on it yet.

Though its timeline of when it expected to hand over the fixes for final FAA approval has slipped, on Tuesday, Boeing said has conducted more than 800 test flights with the new software and that it had completed a “dry run” of a certification test flight. Boeing’s update helped its stock recover and shares were trading up more than 2% on Tuesday morning.

It expects regulators to approve the plane for flight in the fourth quarter.

Improving safety

In the wake of the crashes, Boeing last month announced a series of changes to its structure aimed at improving safety. For example, it said it would add a safety committee to its board, streamline engineering oversight, reexamine flight deck design, among other changes.

Lawmakers questioned FAA officials in several hearings about the 737 Max and whether its relationship with Boeing was too cozy to provide an adequate safety review. The FAA routinely allows manufacturers to conduct some of the work of certifying aircraft.

A 51-page review by international air safety regulators, commissioned by the agency, released earlier this month found that more certification work for the 737 Max was outsourced to Boeing than originally intended. “FAA involvement in the certification of MCAS would likely have resulted in design changes that would have improved safety,” the report said.

Is compliance enough?

The report called for greater staffing and oversight of certification, a key issue as airplanes become more automated and complex.

“One of the questions that this raises for me is whether reliance on compliance is sufficient,” said Christopher Hart, former chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board, who led the team that produced the report. “You can be in compliance and not necessarily be safe.”

Aerial photo showing Boeing 737 Max airplanes parked at Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington, October 20, 2019.

Gary He | Reuters

While international regulators in Europe and Canada have had their own questions about the plane, the FAA, which first certified the planes in 2017, to be cautious.

The FAA is “going show a little bit more distance this time,” said John C. Coffee, Jr., director of the Center on Corporate Governance at Columbia Law School. “They’re scared that they’re being perceived by the world as the captured regulator.”

Pilot training at issue

Another issue that has risen from the MCAS failures on the two crashes is how to prepare pilots to interact with such highly automated aircraft. The NTSB in September said Boeing overestimated how well pilots would react to a series of alerts during malfunctions, such as on the crashed planes. It recommended Boeing take into account how multiple alerts could startle pilots and hinder their ability to regain control of the aircraft.

“As the automation becomes more reliable then our ability to predict failure modes reduces because there are so few failures,” former NTSB Chairman Hart said in an interview. “How do you prepare a human to encounter situations in real time that they’ve never seen before in the simulator, the role of the startle effect? I’m not sure that our certification process adequately addresses that.”

The U.S. generally requires pilots have 1,500 flight hours experience, except in certain cases for those with military or other specialized training, before flying for a commercial airline. Other parts of the world, however, require as little as 240 hours of experience.

“Maybe we need to think about broader system design and training procedures given a lack of depth in terms of crew experience in some parts of the world,” said Richard Aboulafia, vice president at Teal Group. “It’s impossible to have this conversation without people saying you’re blaming the victim. We have a much bigger and more complicated conversation and people don’t have an appetite.”

Muilenburg under pressure

Investors will be looking for any information about whether Boeing is planning a further shakeup to its management team. Boeing’s board stripped Muilenburg of his chairman title on Oct. 11. The company said the move would allow Muilenburg to focus on getting the 737 Max to service.

Muilenburg, who started out at Boeing as an intern and became CEO in 2015, will be under further pressure when he testifies before Senate and House panels about the 737 Max on Oct. 29 and Oct. 30, respectively. It will be his first time facing lawmakers since the crashes.

Congress will likely question Muilenburg on the aircraft’s design and what it disclosed about the plane to regulators.

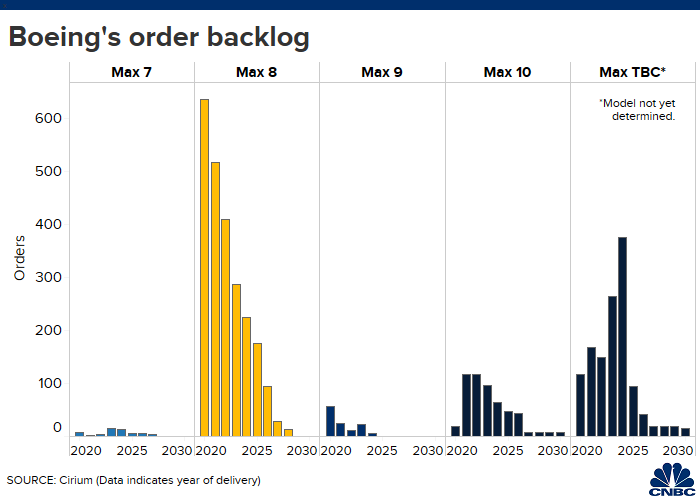

Big backlog

Boeing has a backlog of more than 4,000 of the Max planes. Airlines have canceled thousands of flights and missed out on hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue because of the grounding. Carriers have scrapped their expansion plans as the grounding continues, repeatedly delaying its expected return to service into 2020.

There were some 370 Boeing 737 Max planes at the time of the grounding at March, and more than 300 are on the ground waiting to be delivered to customers.

The 737 has been the backbone of global fleets for decades. Nearly 28% of the world’s global commercial fleet is a 737, including those that are grounded, according Teal Group’s Aboulafia.

The re-engined Max model isn’t Boeing’s only problem. Boeing and rival Airbus are also facing slowing orders for jets — aside from the Max — after airlines around the world stocked up. Now, air traffic growth is starting to slow, which could further crimp appetite from buyers.